The leap of faith – lessons from a veteran journalist

There is a lot of talk about “following your passion” out there. It sounds like simple and obvious advice, mostly uttered by people who have already found their dream job and love it so much they don’t consider it work. Before you can follow your passion, however, you first need to find out what you are passionate about, a task that can be just as difficult. And what if you’re not sure if a newfound interest is your passion? Well, once you’re onto something that has the potential to fulfill you, there is only one option to find out whether it is for you: you need to follow your instinct, take a leap of faith and pursue it with all your heart, even if it means leaving your comfort zone.

That’s quite literally what award-winning journalist Deborah Horan did when she quit law school in her mid-20s in favor of a career in journalism because a book about the Middle East sparked her interest. It was a decision against her parents’ will and against a promising career as a lawyer that completely changed the trajectory of her life.

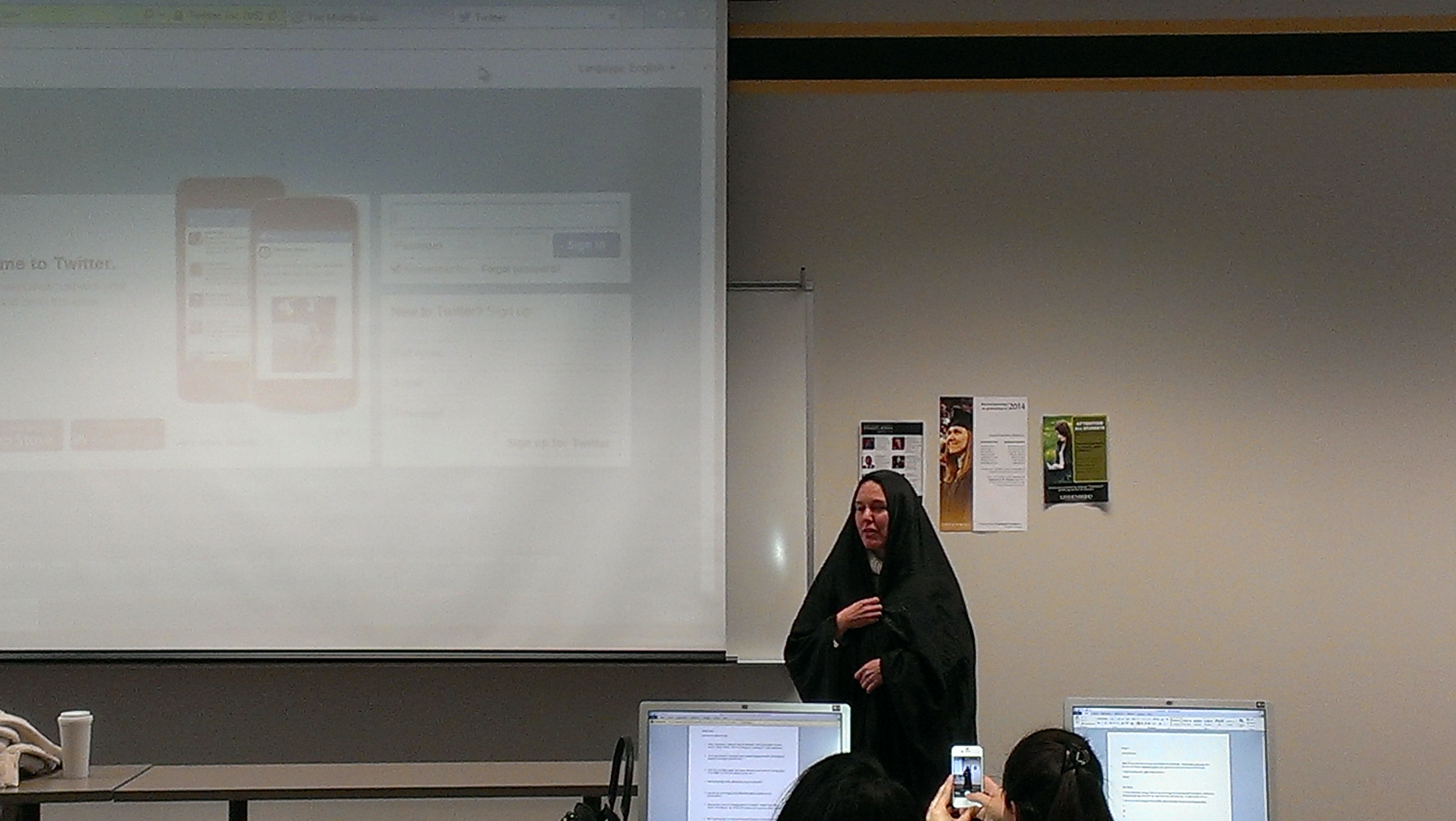

Horan talked to our class at Lindenwood University about journalism, life and everything else.

A lesson in being proactive

Since Horan didn’t have any journalistic work to show for, she traveled through Europe and then stayed in the West Bank and Jerusalem for a while to write a story about efforts by the Israeli Ministry of Justice to declare land in the West Bank “state land” at a time when then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin had declared that some Israelis settlements were “security” settlements and others were “political.” Upon return to the U.S., she sent her article to every major publication she could think of. Her resolve was rewarded when the Washington Monthly Magazine agreed to publish it – in a slightly altered version. But it had her name on it.

In 1993, Horan moved to Jerusalem to cover peace efforts, politics and Israeli and Palestinian society, first as a freelance journalist, then as a reporter for the Houston Chronicle. Being based in Jerusalem, she traveled and reported on and from Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Jordan and Morocco. She said Iran left the biggest impression on her. “It’s a really fascinating place, it’s fascinating politically, it’s fascinating culturally, and it’s very tragic that we don’t have better relations with them.”

After her almost decade-long stint in the Middle East, she returned to the U.S. to work for the Chicago Tribune, reporting on the Muslim immigrant community and also briefly from Iraq twice. One of her articles about a Muslim school in Chicago depicted the students’ effort to find competitors who are willing to accept that no men are in the stands. She said she almost didn’t get a story. “I was already walking away when she told me about how challenging it is to find schools who accept banning all males from the stands. Suddenly I knew that I had a story.”

Tips for being in the field

In term of finding on location sources, the veteran recommended calling local organizations as well as finding out which sources the competition is using and who they are quoting. University professors and journalists working for organizations can also give you valuable information. Above all, you need to be proactive and talk to as many people as possible. Horan said she even hired someone to get access to sources.

Being well connected and going the extra mile allowed her to find many unique stories and write interesting articles such as the one about the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra for the Tribune.

Online journalism is “uncharted territory”

Horan’s former employer, the Chicago Tribune, did not have an online team until 2007. She said many journalists of the long-established media company felt like they were a sort of dinosaur all of a sudden as they had to compete with novel and innovative media outlets. “It was surprising, because the Tribune had always been such a repescted news source”, Horan said. She was laid off in the following year, as the circulation of Chicago’s beacon of publishing had dropped dramatically.

The setback led to assignments for the Office of the Special Inspector for Iraq Reconstruction and the World Bank, for which she wrote communication material for projects overseas and international development. Her animosity towards social media didn’t change over the years. She still hates tweeting (“it doesn’t come naturally”) and although she has a Twitter account, she deosn’t know her Twitter handle. Regarding online journalism, Horan said the story itself doesn’t change.

Nobody can escape his origin

One of the most important lessons of reporting from a foreign country is realizing that journalists report from their worldview, Horan said. “I don’t think there’s any reporting that is completely objective. You always bring your culture, your language and your worldview to a story, not just Americans, everyone does that. […] I don’t think objectivity actually exists.

However, the seasoned journalist said that your worldview morphs over time, which is why reporting from the country directly is so important. “the longer that you are in a place, I started to see things more from an Israeli point of view or from a Palestinian point of view instead of just an American point of view.”

It’s about who you know

Horan acknowldged that she got all of her jobs thanks to people she knew. She also said that now is the time to try new things and have diverse experiences because now is the time when we don’t have a lot of obligations and responsibilities. “When you’re in your 20s you have the opportunity, because you don’t own a house, you don’t have a mortgage, no kids, so if you are on the wrong path you need to change it.”

Takeaways for future journalists

The experienced writer, editor, journalist and speaker shared many valuable lessons with us. Salaries at newspapers aren’t very good. Organizations like the Center for International Media Assistance pay a lot better. Our 20s is the time to get going. We ougt to get some identity capital (like she did when she wrote the article so she had something to show for). We should network as much as we can (so-called weak ties are more important for your career than your friends). We need to develop your own sources and look for unique stories. We should be proactive and curious.

And last but not least: we have to trust your hearts, follow our instincts and believe in ourselves. After all, Deborah Horan is living proof for one of the most important lessons college can teach us: it doesn’t matter how much we know, we just need to be willing to learn. And drink beer with journalists.

Tags

chador, Chicago, Chicago Tribune, Deborah Horan, Egypt, freelance journalism, freelancing, Houston Chronicle, Iran, Iraq, Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra, Israel, Jordan, Journalism, Lebanon, Middle East, Morocco, Muslims, Office of the Special Inspector for Iraq Reconstruction, Palestine, passion, Syria, Twitter, USA, World Bank, worldviewRecent Posts

Deutsche Welle – German bank blacklist of Yemeni nationals widensbenjamin - 02 May

Deutsche Welle – German bank blacklist of Yemeni nationals widensbenjamin - 02 May Deutsche Welle – The future of driving is (almost) herebenjamin - 02 May

Deutsche Welle – The future of driving is (almost) herebenjamin - 02 May A Reading Guide to the Accountability of Humanitarian Aidbenjamin - 02 December

A Reading Guide to the Accountability of Humanitarian Aidbenjamin - 02 December